TRUTH MATTERS… Donate to support excellence in student journalism

Sunlight glared onto the vibrant city of Guadalajara, Mexico, as temperatures stayed in the low 80s through the Winter. Only seven at the time, senior Jesse Quezada, constantly visited his family and rejoiced as he spent time with his cousins.

The language barrier between his two worlds didn’t stop him from enjoying their company. Slowly, however, he noticed a struggle attempting to translate the Spanish language– despite spending so much time around it. Ultimately, this language barrier went unnoticed.

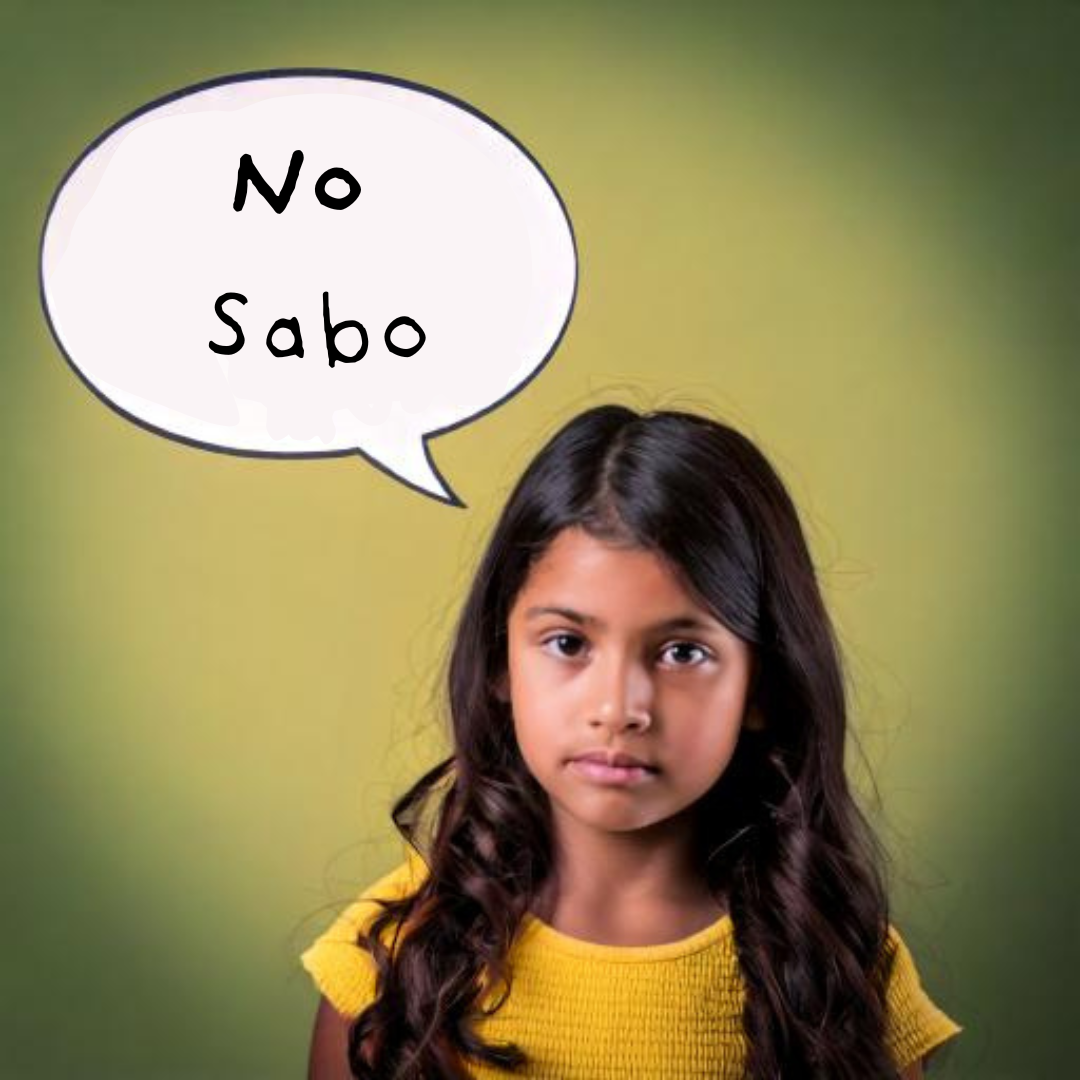

Now labeled as a ‘no sabo’ kid, Quezada shares how being unable to communicate with the Hispanic half of his world overshadows the other half.

Growing up as the child of Spanish-speaking parents, constantly surrounded by a language you have difficulty understanding, can make you feel odd.

In order to label similar individuals, Hispanic and Latino communities coined the term ‘no sabo,’ describing those with difficulty understanding Spanish. The term ‘no sabo’ translates to “I don’t know” in English, with the joke being that the term is a grammatically incorrect translation.

It quickly became a way to distinguish fluent and non-fluent speakers. As time progressed, a ‘no sabo kid’ became a way for fluent speakers to make fun of kids who couldn’t speak Spanish very well.

Regardless of the simple intent behind the title, the root of ‘no sabo’ affects those who had no control over what they were and were not taught, negatively impacting their ability to communicate with family and others.

“My parents tried helping me, but eventually just stopped correcting me all together,” Quezada said. “That’s when it really went down hill. I made common mistakes and my parents eventually just grew to understand what I was saying, even with mistakes.”

Being able to communicate with family was an obstacle for Quezada and demonstrated to be an interference when attempting to build relationships. Younger kids who are fluent in Spanish often ridicule those who can’t because of the inherent idea that they ‘should’ be able to speak it.

In his experience, along with many others, parents choose not to teach a second language to a child who will grow up in a country where English is the primary form of communication.

“My parents even adopted the words I would misuse or say incorrectly, so I never learned to speak the formal way.”

This caused a rift between his two worlds. Like Quezada’s experience, Spanish becomes lost through generations due to adapting to new forms of communication; even if it means being unable to connect with one’s history.

“My sisters don’t really make fun of what I can’t say but it’s my accent that they clown on,” Quezada said.

The older that Hispanic or Latino kids get, the easier it becomes to maintain English as the default form of communication. Most of the time, this goes unnoticed in a country that prefers being able to communicate in a particular language.

However, not all places in America use English as their main form of communication.

“It all really came to my head when I got to high school,” Quezada said. “I took Spanish for Spanish speakers because I thought I was a natural, but I guess not.”

For many students who aren’t fluent in Spanish, a second language class is just part of the tedious curriculum. For Quezada, it was supposed to be a way to show that he was more fluent than he thought himself to be.

“My parents actually made no attempt to teach me Spanish,” Quezada said. “They wanted to make my life as easy as possible.”

Places like the San Fernando Valley flourish as a predominantly Spanish-speaking community.

“My parents wanted to name me Jesus, after my dad, but everyone just calls him Jesse because it’s ‘easier’,” Quezada said. “So they just named me Jesse before anyone else could change it.”

One’s identity slowly becomes warped as they grow and the nickname ‘no sabo’ diminishes the efforts of kids trying to hold onto their heritage and still navigate through a life of speaking English.

Jon Heidenreich • Apr 2, 2025 at 7:46 pm

I mean, come to Mexico, a majority Spanish speaking nation,

AND THINKING you can pass off as a foreigner that doesn’t know Spanish while looking like a native indigenous indian ….

And BOTH your parents speak Spanish ? That family’s IQ is definitely in the negatives.