Hollywood is as much a technological enterprise as it is an artistic enterprise. It’s impossible to escape the large swath of CGI that envelopes us with billboards and trailers for movies whenever we just try to live. Despite how recent this problem feels, however, digital effects stretch back to nearly 50 years ago, and involve an unlikely collaboration of extraordinary minds.

Back in the late ‘70s, there was a computer team based out of New York that was trying to improve the decades-old process of animation in films. The four men that made up this group loved computers and loved animation, so this goal of theirs was almost a natural calling for them. Four years later, their size tripled, and they had produced their first film, Measure for Measure.

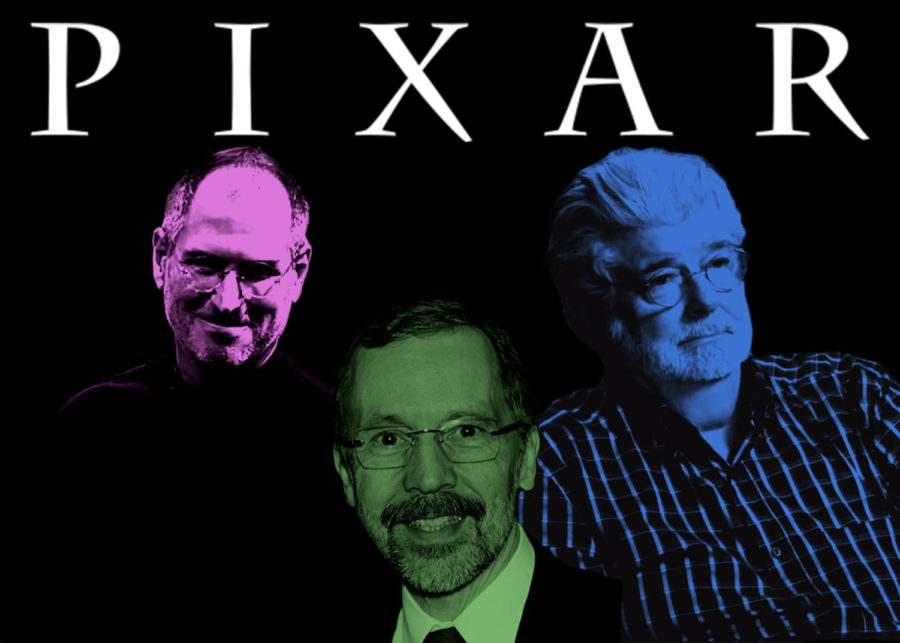

The next year, George Lucas ended up hiring them and making them part of Lucasfilm’s Computer Division. This team was put to work creating computer graphics for films, working on various films for both Lucasfilm and outside studios. In 1983, however, Lucas found himself in financial trouble, and had to find a buyer for parts of his Computer Division. Three years later, Lucasfilm finally sold the computer animation team to none other than Steve Jobs.

The business side gets a little wacky here, but basically, Steve Jobs was able to give this computer team (which had grown substantially since Lucas’s hiring of them) the financial freedom they so desperately needed in an era where computers were as big as rooms. In turn, this team reshaped itself into an independent company that would grow and flourish over the next few decades: Pixar.

This is not the story of Pixar, however. Rather, this is a story of a literal product of Pixar – probably the most important product that the animation company has ever released.

Before Jobs’s purchase of Pixar, Lucasfilm’s Computer Graphics Division used a complex computer program called Reyes to animate and render digital movie scenes. However, when Pixar started hiring actual artists to assist in the development of CGI films, they found out that they couldn’t intuitively use Reyes to start animating characters. Reyes was not built for former Disney animators like John Lasseter; it was built for people with PhDs in computer science like Ed Catmull (who was one of the four men that made up the original team). There had to be an animation program created specifically for animators, but with the computing power robust enough to make any computer scientist proud.

Enter RenderMan, Pixar’s solution to this problem. It made rendering (creating final pictures from a set of computer data) much quicker, and it provided more options for effects animators could choose to add in each of their scenes.

Meanwhile, on a broader scale, Pixar was still trying to figure out exactly what type of computer animation company it wanted to become. Did it want to keep creating computer-animated scenes for outside companies? Did it want to accomplish its original purpose, to create 100% computer animated movies? Or did it want to savvy up its business side by selling computer hardware and software to the open market? In the end, it tried all three, advancing their third initiative by selling RenderMan to consumers.

That decision to put RenderMan out into the market may have been one of the most consequential actions in entertainment history. Any movie you watch today, regardless of which studio it came from or who directed it or how much it earned at the box office, probably has at least one digital scene created by RenderMan. Over the past 30 years, RenderMan’s effects have shown up in nearly every blockbuster franchise, from Terminator to Avatar to every installment in the MCU. And out of the last 30 awards presented in the visual effects category at the Oscars, RenderMan has helped win 27 of them.

The most fascinating aspect of this story, however, is the way different disciplines, people, and organizations converged together at one point to create this digital revolution. Although Hollywood was bound to collide with the technology sector sooner or later, who would have ever thought that then-corporate-embarrassment Steve Jobs would finance the making of better computers that could support Renderman? Who would have ever thought that Pixar, a company who would later turn to making “kid movies” as their main source of revenue, would create the program responsible for nearly all of the best visual effects across the film industry in general? Who would have even thought that the four men in the original team, who wanted to improve the animation process, would get hired by George Lucas to focus on a different initiative – which was the spark that started this whole story in the first place?

This alliance had such a widespread impact on how we perceive and consume entertainment today. If this rather unlikely chain of events hadn’t taken place, I doubt that we would have the sophisticated digital effects that we have now. Or, if nothing else, we wouldn’t have the CGI crap to hate on whenever someone goes overboard with artificial intelligence.

You can find the full list of films that used RenderMan here: https://renderman.pixar.com/movies